|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Improving urban services:

|

|

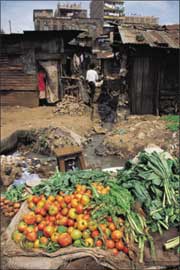

| Market merchandise, Mathare valley, Nairobi (click for a larger image) (c) Crispin Hughes/Panos Pictures |

Case study: Nairobi - Part 2

Open sewers run down the centre of many of the roads, overflow in the rain, and sometimes infect the water supply. Where the city's sewerage system has been expanded, there have been measurable improvements in health and the environment. One large improvement has been to the water quality of the Nairobi River. Despite efforts to increase rubbish collection, the city authorities are only able as yet to dispose of 20% of the total refuse generated. Further efforts in improving sanitation are planned but require money.

Many houses in the settlement are built from mud, boxes or plastic sheets, with corrugated roofs, and usually consist of just one room. Built close to each other, there is little privacy or chance to prevent the spread of disease. Efforts to increase the supply of affordable low cost housing has had some success, but many people were unable to find the deposit required or to maintain the income to support the payment of rent, so that most occupiers of low cost housing appear to be from the higher wage earners. There is still a high proportion of rented accommodation.

Kenya has 50% of its population unemployed and most of these people live around Nairobi. To try to reduce the number of unemployed people in the settlements, a project providing market stalls was initiated. So far this has not been successful however, because planners had failed to allow for the training of potential stallholders in credit and business methods. Most forms of employment are temporary and low paid within the shanty. Small stalls selling food, or scrap and other waste products scavenged from rubbish tips are common. Some jobs are termed sustainable because they encourage the recycling of waste, which is then turned into household objects using local skills. Known as Jua Kali (Hot Sun) enterprises, these self-employed craftsmen work by the side of the road. Some of their objects are beginning to find their way abroad via charities that encourage fair trade from local cooperatives.

|